Maria Montessori saw clarity through the noise.

- The noise — decades of education to teach her about how to preserve the order of so many things, a level of education that would clutter most brains and leave people with little room for originality and creativity.

- The clarity — the observation that education itself is broken, that education doesn’t teach skills that matter, and that perhaps the most essential skills of a life of excellence cannot be instilled or covered by a test.

Born in 1870, Montessori did not limit herself to what society (or her father) expected of a girl.

Maria first attended an all-boys technical school with plans to become an engineer, a profession then (as now) dominated by men. At 13, she opted instead to prepare for a career in medicine that would make her one of Italy’s first female doctors.

With a little nudge to the admissions committee from Pope Leo XIII, Montessori became the first female attendee at the University of Rome Medical School. While there, her male classmates refused to work on their lab assignments with her, so each night Montessori would return to campus alone, completing her coursework under gaslight.

Her casting off emerged as its own possibility, giving Maria the view of a different world, far flung from the prospects of the straight and narrow life her classmates dreamed about after Medical School. During the daytime, she began working at a psychiatric clinic in an impoverished area of Rome, first as a volunteer and then as a director.

It was there that Montessori first questioned teaching methods, developing her observational skills as she tested leading theories of education for their success. Montessori observed that the teachers at the clinic were emphasizing rewards and punishments for intellectually-disabled children, placing external pressures on children who would or could not exactly fulfill external wishes. In taking theories and applying them in a clinical setting, using her training in ethnography, psychology, and medicine to observe outcomes from various educational theories, Montessori approached education with a scientific rigor that previous experts in the subject lacked.

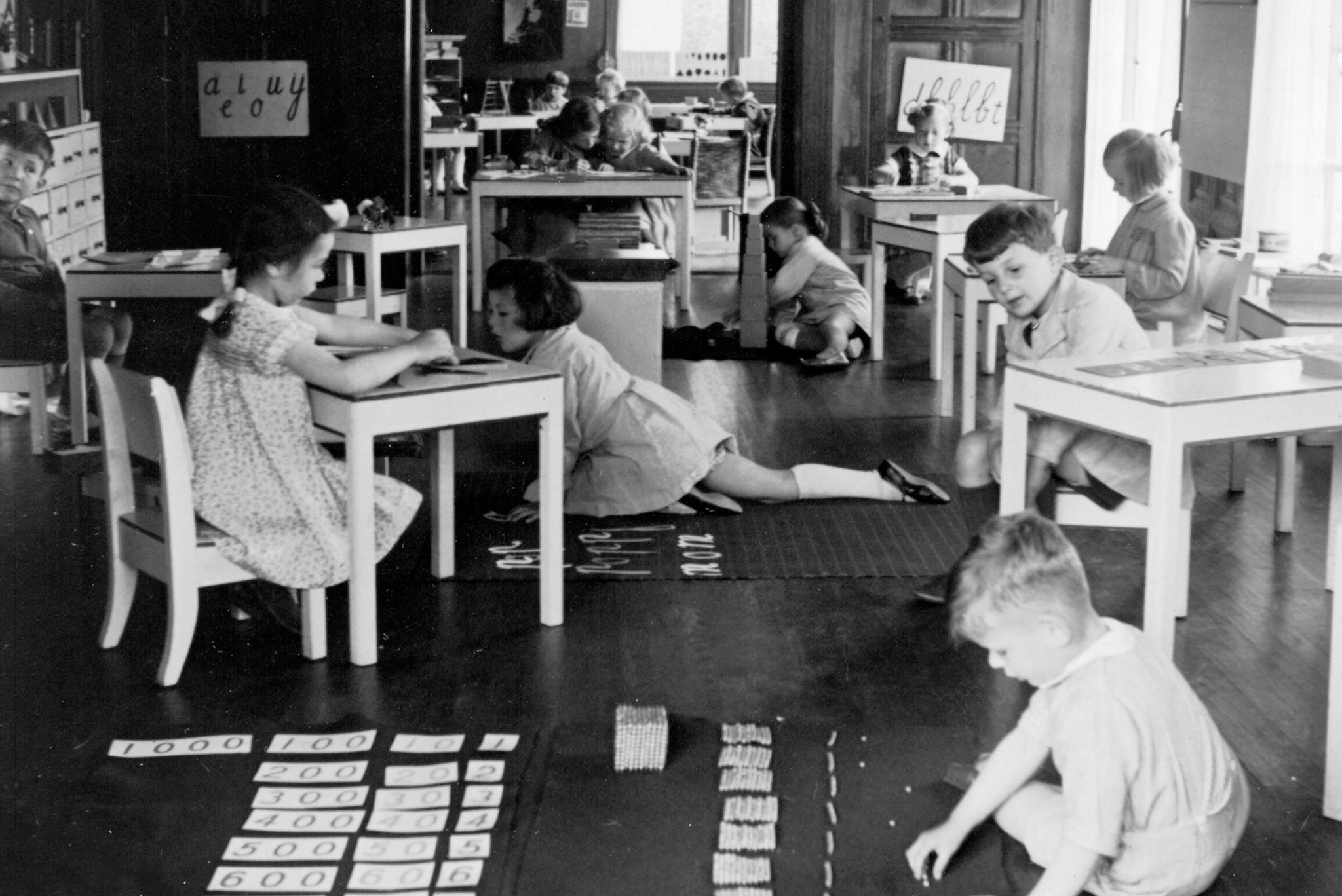

In 1907, Montessori opened her first school in the same area of Rome. Foregoing a career of practicing medicine, she tested out the thesis she would refine over the course of her lifetime. Her iconoclastic methodology produced results that were noticed and replicated, first in Italy and then worldwide.

By 1925, over 1,000 Montessori schools opened in the United States, with many more hundreds across the globe.

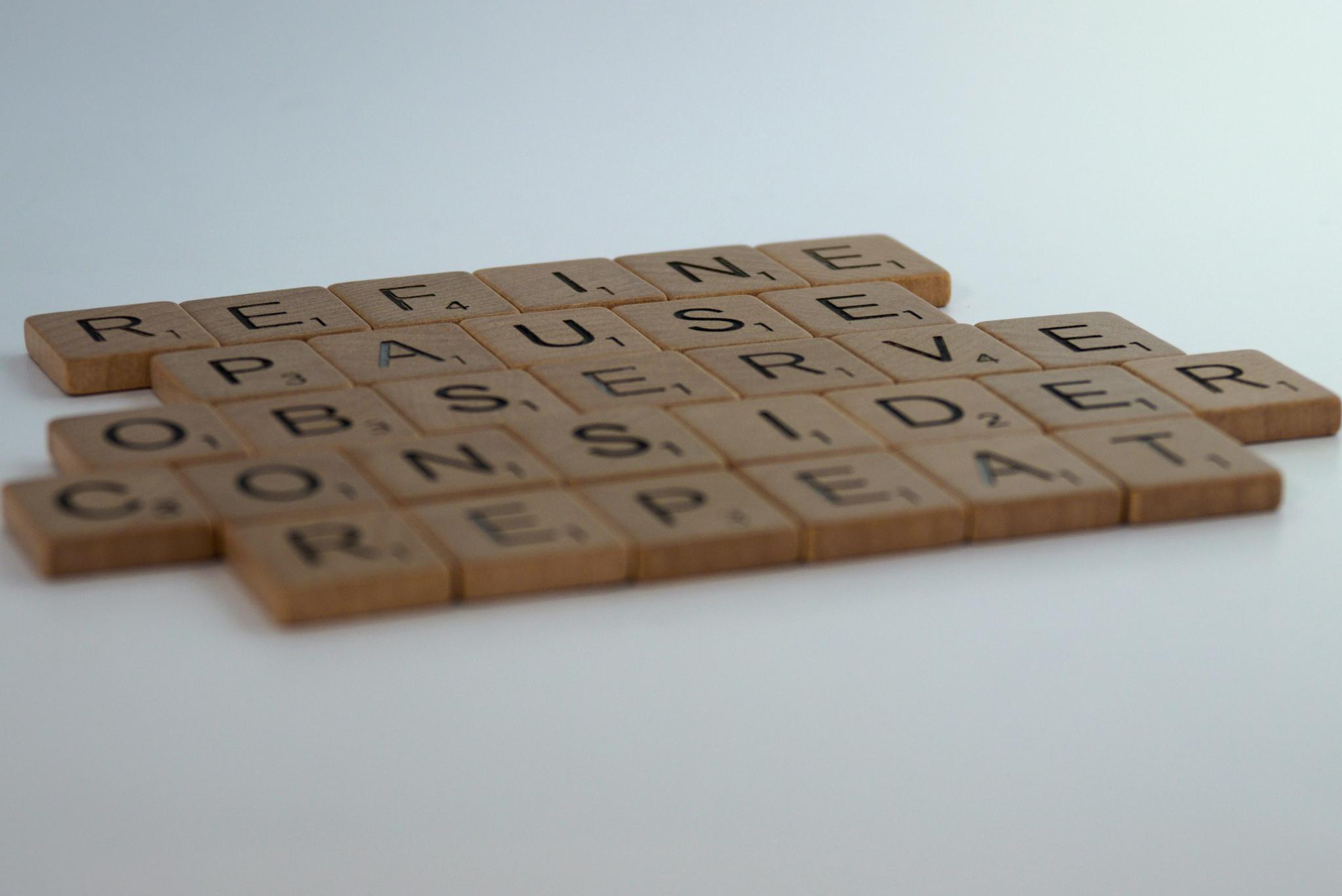

Montessori engaged in observation and refinement of her vision to drive improvements in education. It’s an ideal I aspire to — one of deep immersion in your environment to experiment and iterate and evolve and test new ideas to find a truth that others do not see.

I spent the better part of the first 21 years of my life in organized education, so I’d like to think that I know its traditional focus: tests, memorization, routine. A few years ago when my daughters were applying to colleges, I gained a new perspective on education after learning more about Montessori.

While I’ve heard much about the Montessori method over the years from parents who sent their kids to Montessori schools, I never thought much about Montessori specifically. Every story about the Montessori method sounds better than the last — lots of conversation between kids and between kids and their teachers, self-directed learning in a classroom setting that encourages kids to paw at toys and puzzles they are curious about, respect for chores and the cleanliness of their space, and lots and lots of games (including understanding the importance of following the rules of the game, while allowing competitiveness and a pursuit of winning).

There was even buzz a few years ago about the so-called Montessori Mafia that attributed the creativity of tech pioneers to their early schooling.

And yet for some reason, it never entered my mind to send my daughters to a Montessori school, let alone to understand what lies beneath the Montessori philosophy.

Which is why I was surprised to find Maria Montessori as the author of a remarkable list that speaks directly to my thoughts on education, and to what skills define greatness in the world. I’ve included Montessori’s list of “Personal Qualities Not Measured By Tests” below:

⦿ Creativity ⦿ Critical Thinking ⦿ Resilience ⦿ Motivation ⦿ Persistence ⦿ Curiosity ⦿ Question-asking ⦿ Humor ⦿ Endurance ⦿ Reliability ⦿ Enthusiasm ⦿ Civic-mindedness ⦿ Self-awareness ⦿ Self-Discipline ⦿ Empathy ⦿ Leadership ⦿ Compassion ⦿ Courage ⦿ Sense of beauty ⦿ Sense of wonder ⦿ Resourcefulness ⦿ Spontaneity ⦿ Humility

Wow — quite a list!

This list encompasses the personal qualities that I most aspire for my daughters to possess with plenitude — traits much more important to me than being a master of calculus, organic chemistry, or coding (notice it doesn’t include intelligence). I’ll go even further — Montessori listed qualities that are the “x factors” possessed by people with an entrepreneurial spirit. And, unsurprisingly, Montessori herself was a prime example.

She realized that the inner drive of children was missing from the equation. Hence the traits she listed, which look different from person to person but appear nonetheless given the opportunity for its cultivation.

Out of one domain (care for handicapped children) and into other (general schooling), Montessori developed the sort of cross-functional learning feedback that entrepreneurs dream of.

What’s more, her method speaks to the heart of the entrepreneurial spirit: your natural interest in a subject brings out curiosity, inquisitiveness, joy, challenge-seeking, and innovation. And her process, in its critical study, questioning, and experimentation, was entrepreneurial through and through.

Her commitment and methods were consistent with the ideal she pursued. Where prevailing educational philosophy saw control, Montessori saw self-discipline. Where tradition saw order, Montessori saw imagination. And where orthodoxy insisted on setting cookie-cutter standards for kids, Montessori raised her students to their self-directed purpose.

How fascinating that this genius came from someone steeped in the classroom experience — that someone who could easily have said “this is just the way it is” said instead “it should be better, and we need to think about it in an entirely new way.”

Today and everyday, we would all do well to celebrate Montessori by understanding the significance of her commitment to experimentation. And we would all do even better to continually learn and practice the other Montessori Method.