The corporate matrix is dead.

As the coronavirus crisis has set in, workflows are transitioning to asymmetric and entrepreneurial teams, especially at tech companies.

Many organizations elsewhere have failed to get rid of the corporate matrix. The matrix creates dual reporting relationships for a single employee — one functional, one product-oriented. Ideally, the structure facilitates greater operational flexibility than the military-style chain of command hierarchy preceding it. Divisions within the matrix are supposed to act as microenterprises, exposed to and changing with market conditions.

In many matrix organizations, the reality is different. Work priorities are unclear and decision-making is slow. Parts of the matrix protected from market forces — like HR or communications, for example — take away from the resources given to other parts of the organization while sometimes also hampering the ability of money-making parts of a business to stay competitive. Dual reporting for value creators, managers stuck with advisory responsibilities, and siloed parts of the business threaten the agility of an enterprise to solve complex problems.

Today’s remote work mandates that organizations foster workflow clarity and collaborative productivity that a matrix cannot support. Joint Gallup/McKinsey research found that only a minority of employees in matrixed organizations were sure about their role expectations as compared with 60 percent of their counterparts in non-matrixed organizations.

Coronavirus has magnified the unclarity and silo tendencies of matrix organizations. The rounds of layoffs now, as after 2008, tend to the same conclusion. Employees who span the corporate matrix but do not own the value creation process — from middle managers and administrative staff at United Airlines to the customer service representatives at Chase Bank — are the first to suffer layoffs.

Companies realize they must automate and digitize to stay competitive, but a reluctance to change how corporations operate has kept many organizations from making necessary improvements. A McKinsey survey of executives found that 70 percent of digital transformation projects failed, resulting in around $900 billion in corporate waste. Though organizations may adopt an agile sprint team approach to their problems, they remain vulnerable to reverting to the matrix. It’s a matter of digitally transforming cultures, not just hard-wired structures.

The matrix of the 1950s has remained the standard form of corporate organization. NASA inspired the widespread adoption of the matrix in the 1960s after bringing man to the moon. Amid the energy crisis, stagflation, and lacking economic growth of the 1970s, management experts called for alternative forms of organization to turbocharge innovation. In the 1980s, efforts to recentralize strategic decision-making and cut down on parallel structures kept the matrix largely intact.

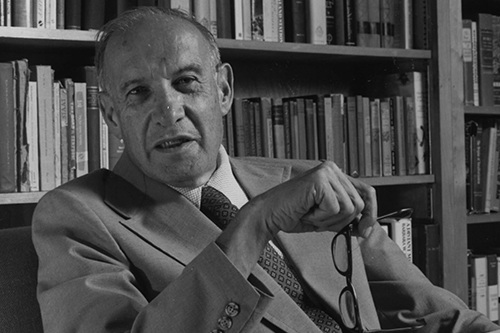

In 1988, Peter Drucker predicted that the information age would make the matrix obsolete in twenty years. Technological specialization would unify separate business functions in a common and rational language of data. Drucker summarized his vision of the post-matrix organization:

Information-based business must be structured around goals and clearly state management’s performance expectations for the enterprise and for each part and specialist and around organized feedback that compares results with these performance expectations so that every member can exercise self-control.

Three decades on, the internal story of the company — despite criticism — has stayed the same.

Why? Why do we insist on promoting something whose prime advocate said would expire twelve years ago? That has been shown, by the counterexample of tech companies, to stifle innovation in a digital world?

Drucker’s prediction of the obsolescence of the matrix anticipated decisions made with data, and precision replacing rote process and structural activity. He saw specialists using data specific to their role. He saw action powered by technology and insight, no longer in need of managerial hand-holding.

As of 2018, Gallup reported that 84 percent of Americans work for organizations that are matrixed. Our workers, businesses, and economy suffer when we lay off middle management in downturns to prioritize the value creating parts of a business only to rehire managers in advisory positions in an upturn (which, importantly, is a primary reason real wages have lagged despite economic growth). Our commitment to the matrix has conditioned the failure of organizations to adapt, and we’re all worse off for it.

I argue that organizations with an entrepreneurial, tech-first, team-of-teams approach have demonstrated a far more stable, efficient, and innovative model of doing business.

- Entrepreneurial: employees must be incentivized and equipped to contribute imaginative solutions to problems they have the skills to solve.

- Tech-first: organizations must lead with and strengthen their technical skills that improve regular decision-making and product delivery.

- Team-of-teams: this approach ties the entrepreneurial and tech-first together. When companies champion a small group of innovative and skilled employees to come up with the solutions they know how to solve, that’s a team-of-teams approach.

With just a few smart people, organizations that have a tech-first mindset give their business the opportunity to transform industries.

Take Square, which provides point-of-sale software to businesses. When Square employees have meetings, one attendee must take notes and store them in a central location readily accessible by anyone at the company. Formal project teams, and the ability to create task forces as needed, have cut down on redundancy in operations.

The agility of centralized information (through shared notes) and decentralized specialization (through teams with precise skills to solve certain problems) enables Square to expand its software (including mobile payments, small business loans, and payroll management, to name a few) and remain committed to its mission to facilitate wider economic participation.

Coronavirus has realized the need for restructuring our organizations. Companies must be leaner, scrappier, and more aligned with how specialists create visible, identifiable value. Already there are shining examples of how innovative companies have created digitally-transformed teams that are quicker to deliver value.

- Cisco set up an internal gig marketplace, where workers may sign up for projects based on their skills.

- As ecommerce skyrocketed, Alibaba created a worker-sharing program to give similar roles to unemployed delivery drivers and retail workers.

- Bank of America converted 3,000 of its employees to customer service representatives as branches closed, tapping into its workforce to transfer skills to needed business areas.

These are just a few examples I know of. Many companies, Uptake included, have found employees to be more productive by shifting towards a digitally transformed sprint teams approach.

Take for example, a small group of Uptake employees with skills across engineering, HR, data science, and corporate development that put together a new industry-specific business strategy.

They generated their own sales leads, sold to customers, and used customer feedback to fine-tune the product roadmap. Another group from a similarly diverse set of skills created our Uptake Scorecard to track sprint team performance across the company and, in turn, enable regular updates on sprint performance so that our leadership team can make data-driven decisions.

These sprint teams shared their experience with their like-skilled teammates and clarified the relationship between different functions at Uptake. In both cases, the cross-functional, time-boxed, clear goal (establish product and market fit, use data from our own teams to make better decisions), and explicit permission to fail promoted a spirit of openness informed by data in the pursuit of greater productivity.

If this trend at Uptake and elsewhere is any indication of a broader movement towards the digital and agile transformation of our organizations, then our new model of doing business will allow us to fight problems piece-by-piece with the small teams of people who know precisely how. And in the era of pandemic, the undertaking of incremental solutions to systemic problems may just be our best bet.